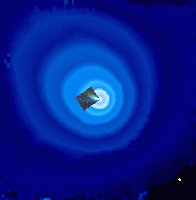

A huge cloud of hydrogen surrounded Comet Hale-Bopp when it neared the

Sun in the spring of 1997. Ultraviolet light, charted by the SWAN

instrument on the SOHO spacecraft, revealed a cloud 100 million

kilometres wide and diminishing in intensity outwards (contour lines).

It far exceeded the great comet's visible tail (inset photograph).

Although generated by a comet nucleus perhaps 40 kilometres in

diameter, the hydrogen cloud was 70 times wider than the Sun itself

(yellow circle to scale) and ten times wider than the hydrogen cloud of

Comet Hyakutake observed by SWAN on SOHO in 1996.

Solar rays broke up water vapour released from the comet by the warmth

of the Sun. The resulting hydrogen atoms shone by ultraviolet light

invisible from the Earth's surface. Even a satellite's view of the Hale-

Bopp cloud would be spoiled by hydrogen around the Earth. Stationed 1.5

million kilometres out in space, SOHO had a clear view.

SWAN is the brainchild of Jean-Loup Bertaux and colleagues at the

Service d'A[e/]ronomie du CNRS (France) and the Finnish Meteorological

Institute. Tuned to see hydrogen, SWAN scans the sky and studies the

solar wind's effect on hydrogen atoms coming from interstellar space.

Comets reveal themselves as local sources of hydrogen.

With SWAN's maps, Michael Combi of the University of Michigan studies

gas outflow from comets. He also uses the Hubble Space Telescope, but

that instrument cannot safely look at comets near the Sun. The unique

SWAN observations of Comet Hale-Bopp imply that the outflow of water

vapour peaked at almost 50 million tonnes a day.

Credits:

Main image: SOHO (ESA & NASA) and SWAN Consortium

Inset photo of comet: Dennis di Cicco and Sky & Telescope

Downloads

- Full-size image [JPG, 137K]

- Medium-size image [JPG, 24K]

- Hi-resolution size image [TIF, 286K]

- Medium-size image [JPG, 24K]